60% of the largest cities in the world are exposed to the risks of storms and tsunamis according to the United Nations Habitat programme. But how are they organising themselves to deal with or face other crises? And to learn from their experience and improve? That is the resilience challenge which borrows some of its solutions from the smart city.

What is a resilient city?

The

United Nations defines resilience as “the ability of [a city] to resist, absorb and accommodate to the effects of a hazard, in a timely and efficient manner”. With increasing urbanisation (more than half of the world’s population now lives in cities), the management of natural disasters, for example, will increasingly have to take account of conditions on the ground that are specific to cities.

Resilience does not focus only natural hazards. The

100 Resilient Cities network, which in May 2016 reached its objective of grouping one hundred participating cities, encompasses in its approach to resilience both occasional crises that may affect a city (an earthquake, an epidemic but also a terrorist attack) and endemic problems (high unemployment, highly

ineffective public services, recurring problems of water supply, electricity, etc.).

The smart city, resilient by definition?

In many aspects, smart cities implement solutions and practices which contribute to making them resilient. The UN Habitat programme has defined a series of

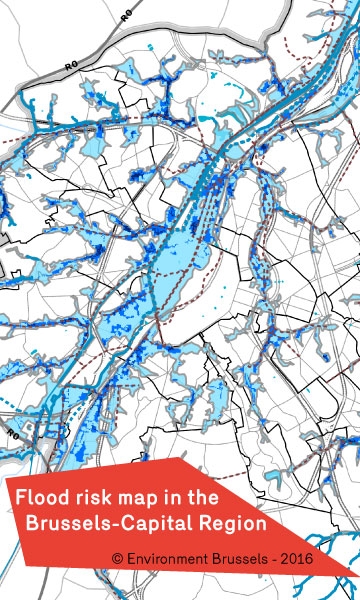

10 essential points which reinforce urban resilience. Among these are the establishment of “early warning and emergency management systems”. At this level, smart cities can rely on sensors deployed in the city. The sensors can be used to detect a rise in the water level, a prelude to high river levels and flooding or to permanently measure exposure to pollution causing chronic diseases.

Video surveillance also has its role to play. The network of video surveillance cameras of the city of Nice, for example, designated a model resilient city in 2012 by the United Nations supplies in real time, images to the municipal crisis centre relating to the risks of floods or storms, to which this coastal town is particularly exposed. In Mexico City, the average call-out time for emergency services teams on the ground has been divided by three after setting up a platform incorporating video images with other data from various public agencies.

The Technologies and Citizens at the heart of the Resilient City

There is another essential measure listed by UN Habitat: “Maintaining up-to-date data on hazards and vulnerabilities … as a basis for planning urban development and taking decisions in this area” and “ensuring that this information and projects in favour of the resilience of your city are easily accessible to the public and that they take part in the debates”. These objectives can be met by solutions which are used to collect and process massive amounts of data (big data) via the sensors mentioned above, to process them and to make them available to everyone (open data).

This is another essential dimension that the resilient city and the smart city share: “participation by groups of citizens and civil society”, which is another measure advocated by UN Habitat, must be encouraged.

Resilient city and smart city: